Fallout: Chengdu

The beginning-to-end-morass that was this year's Hugo Awards may have irreparably damaged the event's reputation; can Glasgow dig it back out?

The 2023 Hugos were mired in controversy from the beginning. It started with a pall being cast over Chengdu’s decisive site selection win over Toronto coming with accusations of ballot stuffing, something that plenty of authors had ideas about.

The Black Trillium author Sam McNeil points out that many in China live along narrow streets that may or may not be marked and that the plethora of ballots missing addresses wasn’t necessarily evidence of ballot stuffing.

Spells of War author Mark McGrath on the other hand not only felt otherwise, he went on to wonder why on earth anyone would have anything to do with a writer’s awards ceremony being held in a totalitarian communist country:

“It should be obvious that a science fiction con, which is supposed to be about open discussion and speculation, can’t function under a government that monitors and censors ideas as pervasively as China does. Fans should find it repugnant to give any support to a government that persecutes minorities and violates human rights on a massive scale. Yet we’ve seen hardly any protests.”

Controversy was ignited anew with this week’s long-delayed release of the full nomination statistics. Science fiction and fantasy fans from in both East and West are up in arms over several candidacies being listed as “ineligible” without explanation, and fear for the reputational damage done to the region and Eastern fandom as a result.

READ THE FULL HUGO NOMINATION REPORT HERE

If the Awards Administration team was hoping to shuffle this out quietly, it didn’t work. News of Worldcon 81’s alleged mishandling of the nomination process has been covered by mainstream news sites like The Guardian and Polygon in addition to a slew of genre sites. This year’s Fan Writer award winner, Chris Barkley, who was actually in Chengdu for this year’s festivities, notes in his account on File 770 that red flags began appearing as early as December 2, when David McCarty issued a message on Facebook that in hindsight sounds like damage control.

After assuring readers that the results had been thoroughly gone through and verified, and remarking that delays were experienced due to smoothing out translations, this is mentioned (emphasis mine):

“The nomination stats are not out yet. We will definitely have them out before the deadline of 90 days post convention, but right now no, I don’t have an expected release date.”

A PDF of the shortlists for each category were posted to the Hugo website the next day, laying out charts detailing the ranked-choice voting tallies. The final page, normally reserved for the complete longlist nomination stats, featured a mostly blank page that invoked section 3.12.4 of the WSFS constitution:

Barkley notes that this seemed odd, since apparently the data had been compiled and was sitting ready for release. The results were eventually published on the last day of that 90-day window, January 19th of this year. The Ineligibles were revealed to the world.

The Asterisk Returns

A few entries deemed ineligible were explained in the report’s footnotes, such as works being published in a previous year in a different language and several alluded to WSFS constitution section 3.8.3, which states that a work or its parts nominated in one category will automatically be eliminated if it appears in another, with the higher voted entry being kept on its ballot. This happened to several works, including the TV adaptation of Neil Gaiman’s Sandman. Season one’s nomination for Best Dramatic Presentation, Long Form was eliminated thanks to section 3.8.3 because episode six of that season, The Sound of Her Wings, had more votes in the Best Dramatic Presentation, Short Form category.

Unfortunately, that episode that was deemed ineligible without explanation.

While speculation continues to rage on even as I type this, the prevailing theory seems to be that the Awards Administration self-censored works before the CCP proper could do it themselves. R.F. Kuang’s Babel, a heavy favorite to win Best Novel, was eliminated despite being a New York Times bestseller and winning Book of the Year at the British Book Awards. However, she debuted with The Poppy War, a trilogy of books that imagined Mao Zhe Dong as a teenage girl, something that likely has not endeared her to Chinese government officials. She has stated on Instagram that “Until (a reason) is provided that explains why the book was eligible for the Nebula and Locus awards, which it won, and not the Hugos, I assume this was a matter of undesirability rather than ineligibility.”

Xiran Jay Zhao, a Canadian author of Chinese descent and nominee for the Astounding Award for Best New Writer, had made statements critical of the CCP in the past. Neil Gaiman has been deeply critical regarding the government’s jailing of artists, and three-time Hugo award loser Paul Weimer had mused in the past that the con was vulnerable to find itself at the mercy of the CCP through quote-unquote “sponsorship”:

“The CCP may not be content with just the already horrible prospect of monitoring the 2023 Worldcon closely. What if they decide to, say, sponsor the Hugo Award ceremony a la Raytheon and Google? Or some other aspect of the con? Chengdu is not going to be able to say no.”

McCarty, in response to all of this, issued what sounded like a hostage statement on Facebook and seems to have gone silent on social media, refusing requests for further comments or interviews. À la The Guardian:

“Nobody has ordered me to do anything … There was no communication between the Hugo administration team and the Chinese government in any official manner.”

McCarty did not respond to a request from the Guardian for comment, but shared what he said was the official response from the awards administration team on Facebook: “After reviewing the constitution and the rules we must follow, the administration team determined those works/persons were not eligible.” He declined to elaborate on what the rules were.

If McCarty’s statements are true, Singaporean native and author of the Saga of the Swordbreaker series Kit Sun Cheah thinks self-censorship is the more likely explanation, even if it meant taking heat from the global sci-fi community (emphasis mine).

“There was no communication, and no need for it. The censors don't have to lift a finger. Everybody knows the laws and boundaries, everybody knows the consequences of running afoul of the censors, everybody has to live under the all-encompassing social credit system. The state need merely make an example or two out of high-profile violators, and everybody else will fall in line. Where the Chinese organizers are concerned, it's better to be seen as inept by the world than to be seen as a threat to the state. Self-censorship carries a lower cost than being censored,” he told me via email.

Cheah went on to explain the significance of maintaining ‘social harmony’ among the State, and its longstanding resistance to curb foreign influences it deems ‘degenerate’. This could not have bode well for a number of artists and writers in mainstream sci-fi, which has pushed hard in recent years to give more exposure to virtually anything or anyone it deemed outside societal norms. Says Cheah:

“Any author who publishes pro-LGBTQ content, advocates for Western-style individualism over Chinese-style collectivism and harmony, promotes racial / sexual / religious identity politics, or otherwise promotes immorality will also be silenced.”

Cheah also believes the Chinese are banking on the controversy fading, saying “The Chinese know that West, with its short-term orientation, will forget this controversy a year from now.”

In The End, It’s The Chinese Fans Who Lose The Most

The reaction from Chinese fans from all of this seems to have been decidedly mixed. Hua Xiaoxi, a neuroscientist and longtime sci-fi fan from Hangzou, told me via DM that an overemphasis on Western/American nominees combined with a tepid reception from native Chinese fans for writers like Kuang and Zhao lead to a lack of enthusiasm among fans she knew. “Some commented that it didn't make sense that Paul [Weimer] didn't get nominated given he had some votes. Lots of users were celebrating the exclusion of Xiran. So it's kind of a mild and mixed reaction.”

According to Xiaoxi, Kuang’s Babel, celebrated by the mainstream in the West, didn’t make nearly the same headway with readers in Asia:

“Kuang had a bit of a mixed reaction from online people and my friends. Babel wasn't read by very many actual Chinese people, which is a problem. Lots of people were even making memes about how nobody cares about Babel.”

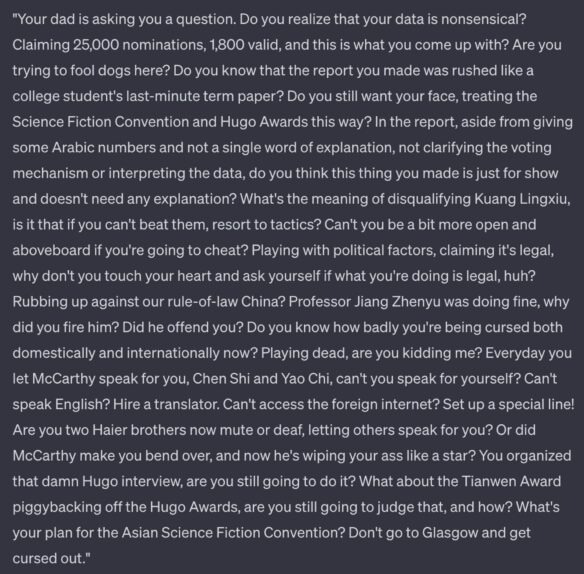

Others however believe the WSFS’s bungling of the awards may have dealt a mortal blow to years of efforts to build goodwill among the West by Asian fandom. One interesting addition to Barkley’s post was several Google-translated screenshots of Chinese fans across various social media platforms who were both outraged and disappointed over how the awards were conducted, even risking some choice words at members of the selection chairs:

Science fiction is huge in China, and from what I’ve read in preparing to write this, its fans and writers alike have been laboring to get its works exposed to Western fans for decades. They’re fully aware of the perceptions those outside the country have of them, or of their government at least, and while there is certainly a case to be made for leaving China out of consideration so long as it remains a oppressive totalitarian state, I have no doubt that the fans involved with this WorldCon would have welcomed some cultural thawing over a shared love of escapist literature.

The organizers haven’t merely run a bad con, they very well could have set fan/writer relations between the east and west back to square negative one. In his recent article for the Straits Times of Singapore, Lim Min Zhang cites several prominent figures in the Asian sci-fi community who are immensely frustrated at the setback:

Chinese sci-fi author Chen Qiufan described the controversy as frustrating and disappointing, and believes it has undone years of hard work by the Chinese sci-fi industry, including writers, fans and publishers, to promote the genre. “It’s causing serious damage to the reputation of Chinese sci-fi,” he told ST, adding that the lack of explanation for the disqualifications was unacceptable. “It will be even more difficult to get published and export our authors and works to the international market because people might have biases and presumptions.”

Zhang later puts into perspective just how much progress is at risk of being lost should the Western market lose confidence in Asian offerings (emphasis mine):

The Chinese sci-fi industry has been on a surge in the past decade since author Liu Cixin’s Three-Body Problem received international acclaim after it was translated to English in 2014. The Chengdu Worldcon was the first time the sci-fi event was held in China since 1939, after a growth in Chinese sci-fi fans helped to secure the required votes at the Washington, DC, Worldcon in 2021.

Can The Scots Right The Ship?

Over the years I’ve contributed to this site, I’ve covered more than a few embarrassing bungles by the mainstream community’s more notable, and supposedly more important, organizations. SFWA near-simultaneously awarding Mercedes Lackey the title of Grand Master before almost immediately cancelling her in the same weekend. Their massive member data breach. Their funding of Pat Tomlinson’s dead-in-the-water lawsuits. SF Canada’s unceremonious and unprecedented ousting of Peter Halasz. The 81st WorldCon in Chengdu towers over them all. No other event in recent history will have the international significance this one will have on how the WSFS and the Hugos are perceived in the years to come. It’s actually impressive in all of its globe-spanning ineptitude. On a more hopeful note, however, it seems Glasgow is already learning from Chengdu’s failures.

It seems like the organizers for the 2024 Worldcon were making some important notes during the debacle. A recent statement on their not-Twitter account that announced the opening of the this year’s Hugo nomination window, mentioned that they would be publishing reasons for nominee ineligibility at the time they issue their final report. With the awards safely back in the country-sized safe space of the UK, surely we’ll all be treated to much more run-of-the-mill milquetoast drama over triggerings or hate speech or some such. Unless something big comes out of it, I’ll be ignoring the proceedings and reading something actually entertaining. Something no doubt indie.

The Hugo's reputation has been dead long before the 2000's. It is a zombie organization now. I used to, even as a teen/early 20's, take the Hugo mark on a novel to be an automatic, "well now I don't have to worry about reading that!" Much like critics and movies. If the critic says, "go watch!" I likely never will.

Like the Oscars, Golden Globes, Mtv Awards, they are not celebrations of excellence of merit, because merit isn't celebrated any more. A sad state of affairs. Far better, I feel, to just get rid of all of those "award" ceremonies, and start from scratch. But, the legacy zombie media has too firm a grasp on them and it will be impossible to pry them from their cold, undead hands.

The Hugos have been a dead award since very late '90s and '00s, when the big publishers (TOR especially) deliberately started to stack the votes to get their darlings wins for marketing purposes.

When the Sad Puppies hit and started pointing out all of the anomalies, they were attacked and called every nasty name in the book. Especially when they tried to prove that the voting could be rigged.

I'm not surprised that the SFWA sold out to the Chinese censorship machine, even passively. For a lot of them, it's their natural home.