Howard Andrew Jones: New Edge Barbarian King

The Sword and Sorcery genre's greatest exponent talks bringing his Hanuvar universe to longform, preserving the pulp ethos, and the importance of the 'New Edge' manifesto 15 years later.

Howard Andrew Jones is a man on a mission. His exploits and contributions to not only the fantasy genre but the whole of literary fiction can hardly be understated; savior of the works of Harold Lamb, editor of Tales from the Magician's Skull and Black Gate magazines, and author of nearly a dozen novels, along with a plethora of short fiction.

In 2008, Jones published what would eventually become known as the "New Edge" manifesto in two parts. It was a sorely-needed crystallization that codified the modern ethos of Sword and Sorcery at a time when the scene's relevancy was flagging.

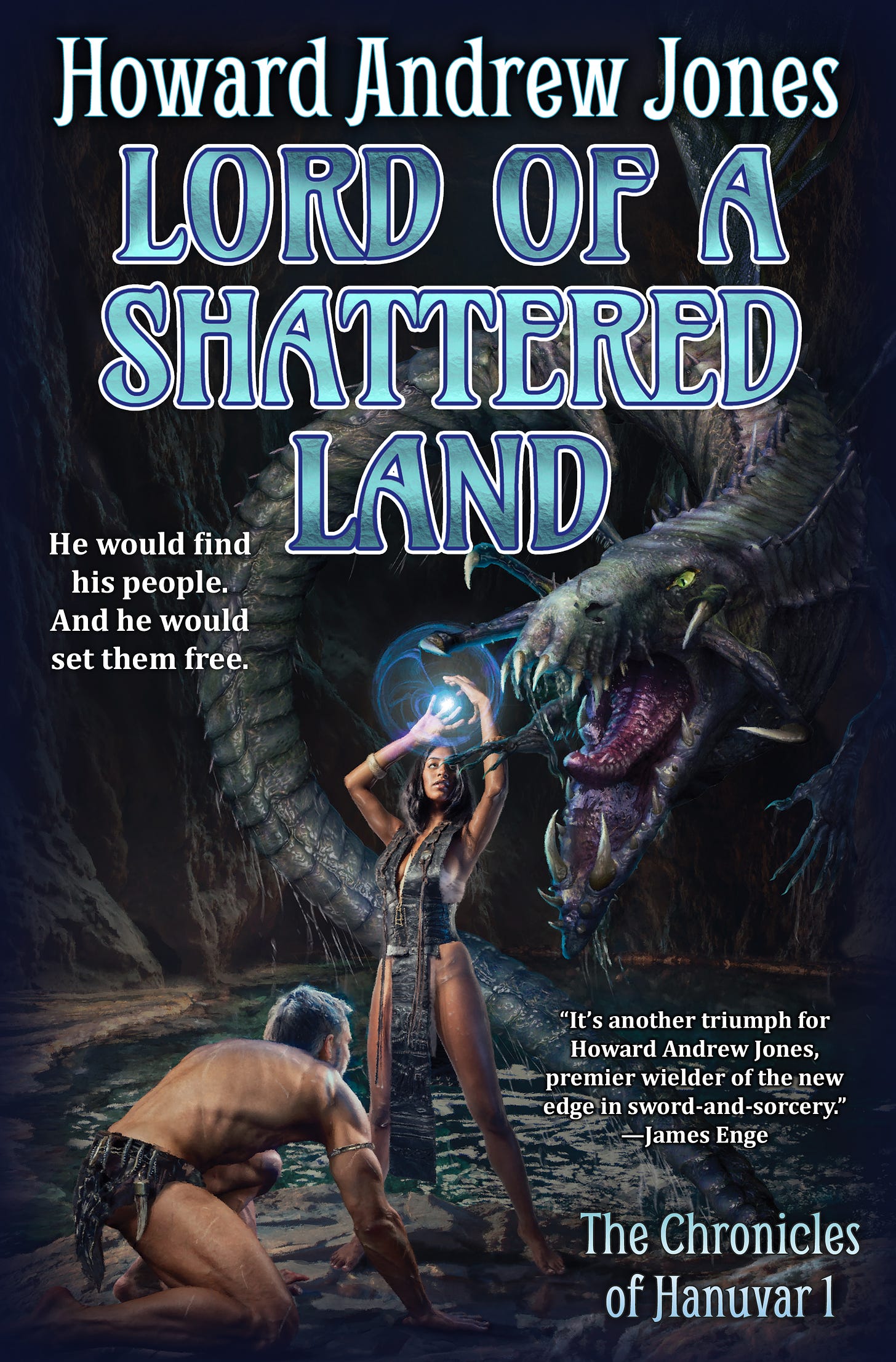

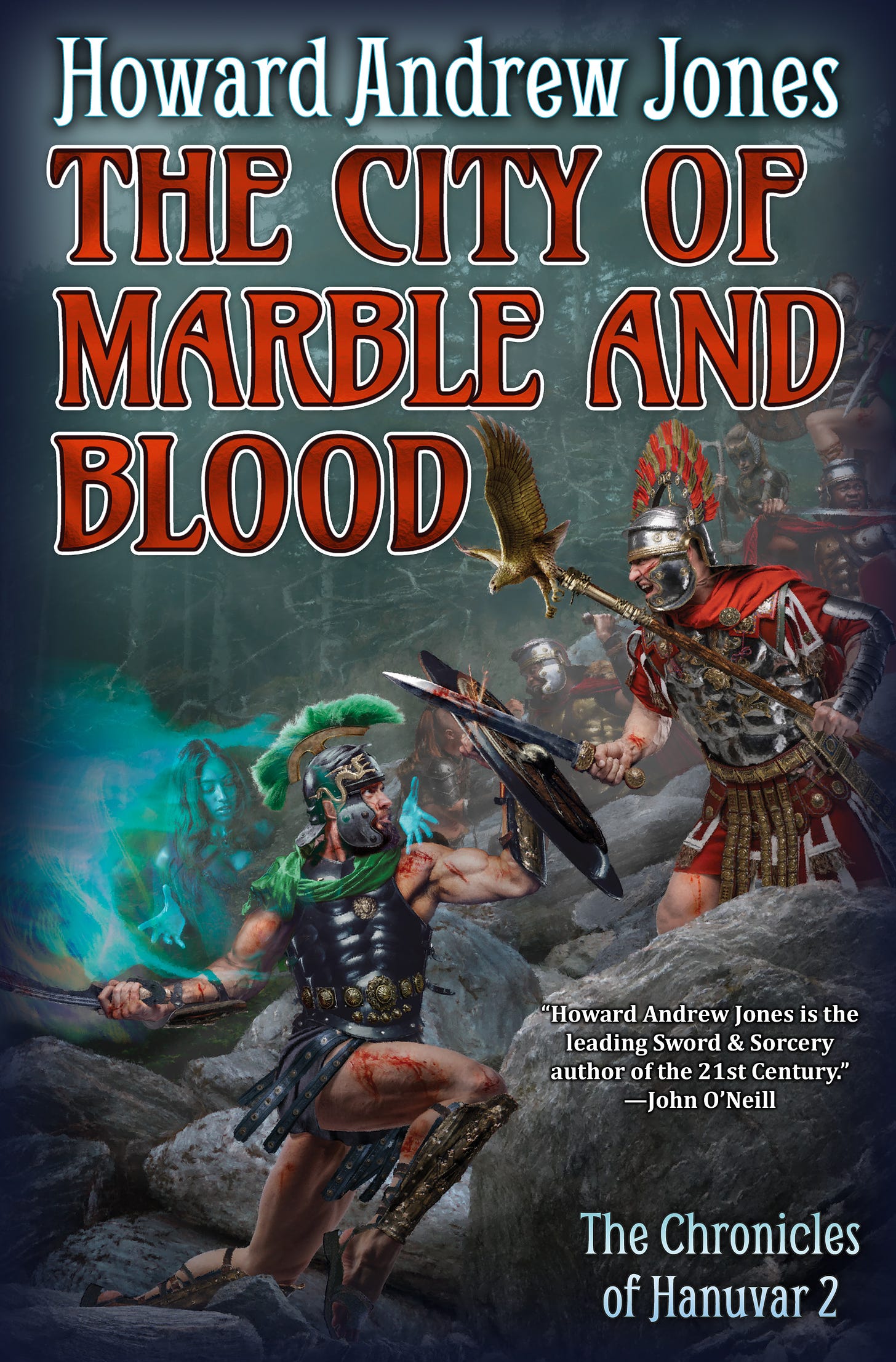

This year, Jones will publish the first two titles of his recently inked five-book deal with Baen, Lord of a Shattered Land and The City of Marble and Blood. His Hanuvar universe, stories set in a world which has only been seen in his short fiction, are finally being brought to a fully realized series of novels. He talked with Upstream about Hanuvar's long quest ahead and the future of Sword and Sorcery.

Q: Congratulations on the new series! While you've been very involved in what it means for something to be called Sword and Sorcery, Hanuvar, your Hannibal-inspired protagonist breaks the mold in a few ways. Can you tell us what's unique about your hero and the world he's in?

Thanks for that, and your wonderful introduction. To be clear, it’s Hannibal of Carthage who’s always fascinated me, not the imaginary mass murdering cannibal guy.

Like most sword-and-sorcery characters, Hanuvar’s not on the hero’s journey that Hollywood seems stuck on. You know -- a young, untried guy who’s forced to leave the ordinary world, learns about his powers from a wise man, comes into his own, and stops the bad guys while winning true love. That’s not Hanuvar. He’s seasoned and experienced and while you get to know his backstory, there’s no slow origin to wait through before things get interesting. You start with him at the height of his abilities.

He’s no brash youngster, he’s middle-aged. He’s not out to prove anything and he doesn’t need to find himself. He knows who he is. And he’s not interested in self advancement or riches, which is probably the most significant difference between him and the typical sword-and-sorcery lead, because rather than being in it for himself, he’s essentially selfless. For him, the only thing that matters are his people. He’s the last surviving general of the city of Volanus, which was destroyed by the Dervan Empire. His people fought block by block, house by house, until most fell with their swords in hand. Only a thousand or so survived to be led away in chains.

That may sound like the setup for a tale of vengeance, but bleak as that back story is, revenge isn’t what Hanuvar’s about, either. No matter where his people have been taken, from the empire’s festering capital to its most remote outpost, he means to find them. Every last one of them. And he will set them free. He doesn’t expect to survive the process, but he intends to free as many as possible before he finally falls.

I suppose I should also say that Hanuvar’s world has an ancient Mediterranean sword-and-sandal vibe. That’s not that different from the bronze-age feel of a lot of traditional sword-and-sorcery, but is less common in heroic fantasy now than it used to be. Think Spartacus and Gladiator.

Q: There's already a sizeable library of short fiction involving this setting and hero. Was it a challenge to adapt your usual faster-paced stories to a longer story arc? How did you approach this project from a plotting standpoint?

The last thing I wanted was to abandon the fast paced feel of a great sword-and-sorcery story. So I didn’t. From the very beginning I envisioned this character’s adventures as a set of episodes that would build one upon the other. There would be an overall arc, there would be returning characters and ongoing threats, but each tale – now chapter -- has to stand alone.

This objective has sometimes been tricky to pull off but I’ve also had an awful lot of fun with it. Writing this way means I’ve been able to avoid the slow starts endemic to a lot of modern fantasy and just get right to the parts that are fun to write, and read. As a result of this approach, each book is a little like a modern TV series made up of individual episodes. The chapters can be enjoyed separately, but they are almost certainly more rewarding if consumed in order. And like those TV series, each season (or book, in this case) ends with a climactic conclusion that resolves the immediate problems, although some challenges linger on for the next season/book.

Additionally, each book builds upon the one before, creating a larger connected sequence. Book two is more tightly integrated than book one, but that’s by design. Book one. Lord of a Shattered Land, gets you familiar with Hanuvar, his world, and his challenges, before additional complications and details get added to the mix in book two, The City of Marble and Blood.

Q: Some feel that increasing dissatisfaction with modern entertainment, with its incessant remakes and hamfisted messaging, has led to the phenomenon of the “Iron Age” zeitgeist. Many writers and artists, especially among independent fiction, feel we’re on the cusp of a burgeoning Pulp Renaissance, and many are looking back to the old masters like Howard, Rice-Burroughs and Lovecraft among others. What are your thoughts on the movement, and do you agree that there could be a groundswell of fantastic storytelling on the horizon?

I sure hope there’s a groundswell of great fiction on its way. I’ve been looking forward to seeing it for probably a quarter century now. Maybe longer. Around the turn of the millennium it seemed like sword-and-sorcery was almost completely dead apart from the small press, and its presence even there was pretty anemic. It was easier to find parodies of sword-and-sorcery than the real thing. In those days it was snarky irony that kept cropping up in adventure tales – and that can be amusing in small doses in skilled hands, admittedly -- but it had grown tired. It was as though some writers were embarrassed to be writing sword-and-sorcery and therefore wanted to make sure readers knew that the writers understood the genre was beneath them. Fah.

When it comes to that newer problem, ham-fisted messaging, I hear you. Don’t get me wrong – I have opinions and feelings about things, and I know they end up in my fiction even when I don’t mean them to. But story has to come first. If you’re just beating your point home on an anvil then you’ll drown out the worth of anything important you’re trying to say, and the odds are that your characters will feel about as real as cardboard cut-outs with speakers to broadcast your message. Probably that kind of fiction makes the writer and its intended consumers feel pleased with their righteousness, but beyond that narrow audience the story has no staying power because it doesn’t provide much entertainment.

I grew up on reruns of the original Star Trek, and it often seems to me that a lot of modern message fiction writers don’t get the difference between the approach of a good Trek episode and a bad Trek episode. Consider “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield,” from the third and weakest season, where the crew runs into an alien species that is half black and half white, but fifty percent of the population has those features on the opposite sides from the other. Each “race” is filled with hate for the other. The episode does a nice job of starkly rendering racism as absurd, but it’s also fifty-five minutes of the same point being made over and over, and over, with a complete lack of subtlety. Whereas “The Doomsday Machine” is the story of the Enterprise’s haunted sister-ship, its tragic and obsessive commander, and a terrible weapon that has to be stopped before hundreds of millions of people are slain. It’s a masterpiece of tension, suspense, and plotting, with great character moments, and it also touches upon the danger of creating weapons so powerful that we may not be able to stop them from destroying us. Both racism and weapons of mass destruction are worthy topics for discussion, but one tale puts message first and the other puts story and character first. “The Doomsday Machine” routinely makes “best of original Trek” lists and the other never does.

“Never apologize because you like sword-and-sorcery, or let yourself be made to feel ashamed because it isn’t message forward.”

But back to your main point, I’m seeing more signs than ever that there may be a pendulum swinging back the other way. Until recently it’s been the small press where sword-and-sorcery and heroic fiction have taken strength, and it’s a strength that seems to have been gathering momentum because more and more outlets are cropping up every year. This suggests a thirst for the form. (I regret that the modern media landscape is so fragmented, because it seems like some of these writers and movements are doing similar things and are sadly unaware of one another!) We’re seeing more and more fantasy fiction on big and little screens and that’s a good sign. And then I see that Baen, a major publisher, is enthusiastic not just about my work but about a growing library of writers interested in writing tales of fantasy adventure where heroes are front and center. All of this fills me with hope.

Q: As the editor of several fantasy literary magazines, who are some of your favorite new authors out there and why? Who's carrying the Sword and Sorcery banner highest so to speak, who might be flying under the radar?

I answer this question with some trepidation as I fear that any answer I give will unintentionally slight one of the very fine authors who I’ve had the privilege to know or work with. I’ve met a lot of them over the years, both through appearing in some of those small press pubs – in the trenches of the fight to keep sword-and-sorcery alive – and through publishing them.

The most obvious suspect is James Enge, whose Vancian/Zelaznian adventures of Morlock are one of the best remembered things about Black Gate, and led to a six book deal from Pyr some years back. He’s recently cracked some of the major modern science fiction and fantasy markets without compromising his vision in the slightest, and his Morlock work was once nominated for a World Fantasy award, the only true sword-and-sorcery fiction I’m aware of to have come close to a major industry award since Michael Shea won the World Fantasy Award for Nifft the Lean. Then you have Scott Oden, who’s been writing some cracking good heroic/historical fantasy with a true Howardian vibe for at least a decade for major publishers and somehow keeps getting overlooked in favor of the next big fat fantasy series.

“The past was a different country, and it can be hard to explain to young people, or people unused to reading older literature, that different times had different attitudes.”

Already this discussion grows long, and I haven’t gotten to Chris Willrich, creator of the long running Gaunt and Bone tales, or John C. Hocking, writer of the Tales of the Archivist, and Benhus, and, like Oden, author of some of the best Conan pastiche. I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention John Fultz, who has a wonderful updated Clark Ashton Smith/Tanith Lee vibe, and C.L. Werner, best known for a whole slew of great Warhammer fiction but perfectly capable of great original stuff as well, or Nathan Long, about whom I could say exactly the same thing (and who writes officially authorized Lankhmar stories for The Magician’s Skull), or William King, the Warhammer writer who created Gotrek and Felix and who’s written a whole slew of Kormak novels. Then there’s Milton Davis, creator of MVmedia, home to Changa’s Safari and other great sword-and-soul fiction, and Violette Malan, creator of Dhulyn and Parno.

These are just some of the people I know who’ve been around a while. There are all kinds of promising newcomers, or not-quite-as-newcomers, and an entire school of British sword-and-sorcery writers whom I’ve only recently become aware of. If you really want to see sword-and-sorcery prosper, I hope you’ll check out great venues like Tales From the Magician’s Skull, where Joseph Goodman and I publish the finest new sword-and-sorcery tales we can lay hands on. You should also look to other fiction venues, like Whetstone, and Heroic Fantasy Quarterly, and Weirdbook, and Grimdark, and New Edge Magazine, and Cirsova, and Savage Realms, and probably a bunch of others I’ve momentarily forgotten about, not to mention great small press outfits like DMR and Rogue Blades Entertainment. I can’t claim to love every tale from every one of these outfits, nor do I share every opinion in every editorial or post from these other places, but when it comes to fiction these are some of the most exciting places to find what’s new and fresh in sword-and-sorcery.

And of course I hope you’ll check out Baen! For the last few years I’ve been pretty enmeshed in short fiction because of all my work for The Skull, and so had completely missed some of the heroic fantasy coming out of their stables, like the fiction of Tim Akers and Larry Correia, and upcoming work from Gregory Frost.

Q: On the topic of the future of the genre, some speculate that there may be an effort on the horizon to clean away some of the grit that defines the genre, or shoehorn anachronistic elements that mirror modern social neuroses. An attempt was made to cancel Lovecraft last year, Burroughs and Howard could very well be the next targets.

Back in 2008, you wrote, rather presciently, in Honing the New Edge Part 2 at Black Gate that: “To be new, to be fresh, we must throw off the shackles of those who have tried to remold the genre to be respectable, and we must step past those who hoped to de-fang it to apologize for the genre’s faults and bad practitioners.” It seems what’s old may be new again. What advice do you have for writers of fantasy who take inspiration from the same authors you do, looking to preserve the past while not succumbing to the mob pressures of the modern literary scene?

Never apologize because you like sword-and-sorcery, or let yourself be made to feel ashamed because it isn’t message forward. A lot of times the genre may seem to lack a message entirely, but that doesn’t mean there’s nothing of value in a story where characters are shown overcoming a terrible challenge with wit and brawn. Sword-and-sorcery is part and parcel of the mythic cycles we’ve been sharing around the campfire since the earliest days of our species. We’d hear how our ancestors chased down the elusive stag, or fended off the clawed thing in the dark, or guided the tribe to safety through a land of enemies. In listening, we were inspired to emulate courageous action and to not stand idle when times were dark and all hope seemed lost.

While we can model off the wild inventiveness and great pacing and thrill of adventure (and horror!) from the old guard we don’t need to copy some of the old-fashioned shorthand along with it, where THIS culture or ethnicity is summed up as having only these (nasty) characteristics, or where all gay people are weak and useless (I mean, come on – some of the most badass generals and warriors in history weren’t exactly straight), or where almost all women exist only to be handed out as rewards.

We must not throw what’s come before on the rubbish heap. We can acknowledge the differences and some of the instances that make us feel uncomfortable now yet still celebrate what’s great in the older work. Just because some attitudes or expressions in a work are different from modern societal norms doesn’t mean that the work in its original form isn’t valuable or inspirational. Those sorts of things could be said about any literature, past, present, or future. What we should all strive to do is to get at the core of what makes things engaging and enlightening to our fellow humans.

The past was a different country, and it can be hard to explain to young people, or people unused to reading older literature, that different times had different attitudes. Some don’t have the patience to hear the explanation or an interest in reading things that can make them uncomfortable, and while that’s disappointing, I get that it can be hard to find joy in a work where you really don’t see yourself. It’s harder to talk to people when they get shrill about the matter, or when they come in ready to pre-judge, but I try to reach them and point out how anyone who wants to craft a great mass battle needs to read Robert E. Howard’s “Black Colossus” or see how to describe an amazing, memorable sword fighting sequence via Fritz Leiber’s “The Seven Black Priests,” or I discuss the evocative worldbuilding of Leigh Brackett’s fading Mars – and so on. I love this stuff, and I guess I keep hoping that if I can point the skeptical to the things that are magnificent maybe they can overcome their misgivings and find some of the same beauty that still enthralls me.

If you’d like to check out Howard Andrew Jones’s website, check out www.howardandrewjones.com. You can also check out his page on Baen books’ website here.

Solid interview and discussion. I'll link to it in my next S&S Roundup.